Alia Peer and her family deeply understand the connection between fashion and nature. He spent his childhood playing outside on his farm and spending time at the family’s clothing manufacturing company. “When you grow up on a farm, you develop an awareness of the environment and everything around you,” he says. It was here, on the west coast of South Africa, that he witnessed first-hand the effects of environmental degradation, from the impact of agriculture on the soil to the stark contrast between clean rural air and smog when traveling to the country. city.

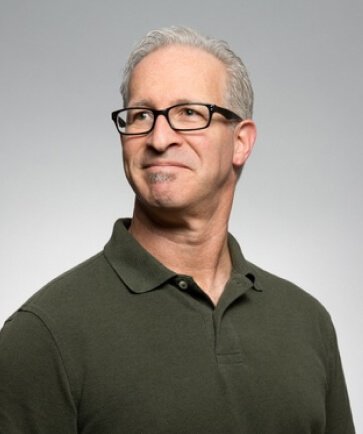

Alia interned at POLO South Africa when she was 16 years old. She then studied fashion in London and now holds the position of creative director at POLO South Africa. Her personal ethos and that of the brand are aligned, creating clothing that is conscious of the environment and the humans who inhabit it.

The brand, led by Alia, takes careful and conscious steps on the path towards a more sustainable fashion system. POLO values locally grown natural fibers, such as its merino wool garments produced in South Africa. It also prides itself on a traceable supply chain, prioritizing nearby manufacturers to help reduce its carbon footprint.

Looking ahead, Alia is considering the full life cycle of the brand’s garments, particularly their impact at the end of their useful life. “Ultimately, we have to take responsibility for everything we produce,” he says. POLO’s AW24 collection is a farm-to-wardrobe project, with each piece made from locally produced merino wool capable of biodegrading at the end of its life cycle. Every facet of the production process for this new collection took place within a 450 kilometer radius, from sheep farming and spinning to tailoring and weaving.

The perfect sustainable fashion system

Even with our best efforts, the “perfect” sustainable fashion system is unattainable, because sustainability inherently goes against the volume-driven model of the fashion industry. Alia doesn’t try to greenwash what is possible; For her, buying and producing locally, as well as encouraging frank conversations between consumers and producers, is a start. While many may lament how the advent of social media has made it easier for customers to interact with brands, she welcomes it. “I think it’s beautiful to talk and talk openly with consumers,

“Consumers are in a very powerful position because a lot of the power lies with an individual,” he says. “I think sometimes we forget: we feel like we’re one person.” For her, a change of mentality is necessary. Instead of thinking, “What’s a bottle when there are over seven billion people in the world?” Imagine a world in which more than seven billion people refuse to accept plastic bags or buy plastic bottles.

The future of fashion

Alia sees a clear divide among South Africa’s youth: one side is conscious about their purchases, while the other embraces fast fashion trends and mindless consumption. It is crucial to address this disconnect between young people, their clothing and the environment. “There is an educational gap,” he says. “We’re here to see what we can do within that space.”

POLO wants to work with young people through schools, as the next generation of consumers. In collaboration with Cape Wools SA, boxes and posters explaining the history of wool, including materials from sheepskin to a knitted product, will be delivered to schools. Additionally, they are organizing screenings of La Voz Del Mar, POLO’s documentary about the Zandi Mermaid, in several schools. “How can you expect children to know the impact of microplastic pollution, for example, if you’re not actually going to talk to them?”

Leave a Reply